From the age of four, it was difficult to get a badminton racquet out of Kirsty Gilmour’s hands.

Realistically, there was never any doubt she would go on to become a professional. Growing up in a family of badminton players, she went to Glasgow’s school of sport to combine training and playing with her studies, but even then what she has accomplished would have been the stuff dreams were made of.

Making her Scotland debut at 16, Gilmour represented her country at the Commonwealth Games a few months later in New Delhi in 2010, and from there she has never looked back.

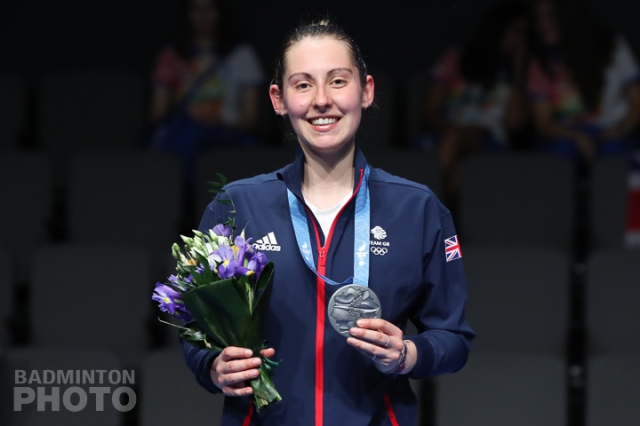

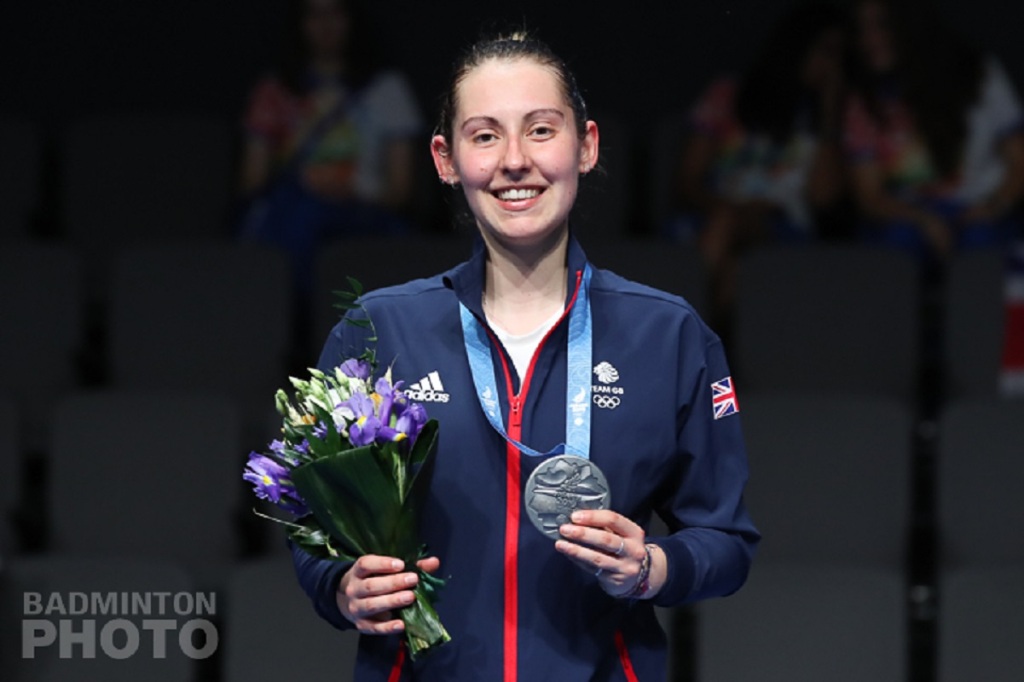

At her home Commonwealth Games in Glasgow in 2014, Gilmour won a silver medal in the women’s singles. Two years later, she reached her highest world ranking so far at number 14 in the aftermath of an Olympic debut in Rio, before winning a second Commonwealth medal in the Gold Coast in 2018 and returning to the Olympic stage in Tokyo last summer.

Things, if anything, only got busier for Gilmour from there. She competed in the Uber Cup in Denmark in October before that country’s national open, also going to France and Germany before rounding off the calendar year with the World Championships in Spain, where Gilmour reached the third round before losing to world number one – Taiwan’s Tai Tzu-ying.

Having struggled with injury this time last year, she was in the rare position of regularly travelling internationally during the pandemic. That gave her insight into what pandemic life was like in each country, but really it was just a relief to be back playing at all.

“Every country that I’ve been to has obviously had its different rules, but we always try and conduct ourselves in pretty much the same way,” she explained.

“We’re living with the highest social distancing level and wearing masks, even when we’re living in a country with an element of freedom. We were in Denmark in October, and nobody was wearing masks outdoors or indoors. Even in coffee shops and restaurants, you just needed to show your vaccination pass, but we would still wear masks so that we could say we’d done everything possible.

“We always functioned in as much of a bubble as possible, so it’s been interesting to see different countries and how they are dealing with it. We’ve just kind of tried to stick to the same things, because we always have the same tournament protocols in place.

“If you’ve got a journey to do, a connecting flight that’s eight hours, then you’re going to be wearing a mask for eight hours and you better get used to it, because there’s no escape. It has been tough, but it has been good and I feel really lucky to have been able to do it because there was a long time without it.

“I remember when the first lockdown happened, waking up on Monday morning and not going to training – that has been my life since I was four. Not full time since I was four obviously, but since I was 11 at high school getting on a badminton court has just been part of my day.

“We went four months with no court training. I was doing shadow badminton, pretending I was playing, in my basement car park looking like an absolute lunatic to anyone that was coming or going to their car. That was the longest I hadn’t hit a shuttle since I was four years old. Even with injuries, it has always been less than that, so the pandemic was the longest I had gone without properly playing badminton.

“It actually gave me a lot of confidence that I can take some time off and be okay, whereas before I would also think I had to do a little bit on court, not have a total holiday and still do stuff.

“In that four months we had a squad Zoom meeting every Monday morning at 9am, we would get our programme for the week and we would have two sessions a day. In the morning that would usually be something badminton-specific, whether that be shadow, sprints or a speed session, and then in the afternoon it would be yoga or home weights. We had assigned reading to do, video analysis to do, so we were still functioning as full time athletes, we weren’t completely on our sofas, we just had a bit more flexibility over when we did those sessions I suppose.

“We were so well organised by our head coach, and the Scottish Institute of Sport – it was incredible organisation from them. I would be a very different person without them.”

The pandemic was one of the first chances Gilmour got in her career to stop and reflect. With it seeming like such a natural progression from her days flitting between Bellahouston Academy and Scotstoun at school to becoming a full international, it was a moment where she could ask whether she really still loved the life of being a pro athlete.

The competitiveness and determination that saw her embrace the limelight in the first place, even through injuries, reassured her that she still very much wanted to play badminton for a living.

She can see, though, how far she has come since competing in a Commonwealth Games straight out of school.

“That was quite pivotal in my career to be given that opportunity at 17,” Gilmour reflected.

“We’ve got much tighter space these days, I don’t know if we would have that spot available to give to a 17-year-old now. There was an element of being in the right place at the right time for sure, but to have that opportunity to go to a Commonwealth Games and play the singles, doubles and mixed doubles – which you only do when you’re 17, that’s madness when you’re a senior player.

“My remit was to play as much badminton as I possibly could, spend as many minutes on court figuring stuff out as I could. My Commonwealth Games experiences after that have been nothing like that.

“After that it was like ‘we have to get a medal here’, so that Commonwealth Games in particular was pretty pivotal I’d say. It is a bit mad, because it was my first bigger multi-sport thing that I’d done. There are so many good things in the UK like the UK School Games – that’s a great little thing. If you take that seriously, that can be such a good introduction to multi-sport events.

“I don’t know if people outside of sport appreciate how different a Commonwealth Games and an Olympic Games are. Every four years we have a European Games instead of a European Championship, and anything that’s got ‘Games’ in it is a multi-sport thing.

“You’re in a village crossing paths with boxers, gymnasts, netballers and other athletes, but anything that’s got ‘Championships’ in it is just going to be badminton, with the same people you see week in, week out.

“I think things like the School Games and the Commonwealth Youth Games – I actually did a full Commonwealth Games before I did a Commonwealth Youth Games – are so important for concentration. That’s the hardest part of those ones, because they’re so busy. It’s like nothing else you’ve ever experienced.

“We’re all bloody sick of the word bubble at this point, but it is just you entering into this little sphere of sport where you’re literally all there for the same reason. You forget to read the news, you don’t know what films are coming out, pop culture goes out the window. It’s just this Games bubble, so things like the Commonwealth Youth Games and School Games were really important for me to switch my brain on and think ‘this is really fun, but we’re here to play badminton’.

“That has ramped up each time from the Delhi Commonwealth Games. Then I could look around and think ‘holy smokes, there’s a lot going on here, this is cool’. Glasgow was different, because it was right here, 20 minutes down the road. Then the Gold Coast was a lot of pressure. I didn’t really see the Gold Coast in all its glory to be honest, that was more head down, let’s get this job done. I did get a cracking tan out of it though.

“Then an Olympic Games – take a Commonwealth Games and multiply it by five scale-wise, people-wise and village-wise. It’s a good taster for an Olympic Games I’d say.”

It was during her schooldays that Gilmour first started questioning her sexuality, but it was not until last year that she did her first interview about being an out athlete on the podcast Out with Suzi Ruffell.

She describes the reaction to her coming out within badminton as “pretty good”, and she has been heartened by the response from fans outside the sport looking in.

“Even with just the little bits of openness that I’ve given, I’m yet to have a bad comment, at least to my face,” she said.

“That’s the best you can hope for, to normalise it. Each individual person that is a little bit open about who they are, I think that’s why people love sport. Okay, it’s the drama of the actual competition, but with social media and everything now it’s about the people and the personalities.

“That’s why people get invested and support you, and as the sport grows the personalities start to come out. That’s the way we’re going now, and I’ve had seven or eight messages since being on Suzi Ruffell’s podcast and doing a few Q&As saying ‘I’m queer and I play badminton, and it’s so nice to see that you’re being open about stuff’.

“That’s pretty cool. It’s no skin off my nose, I’m just living my life and being me, so if some other person takes a little bit of comfort in that and we can all live a nicer, more open life, then that’s a good thing.”

“I don’t know if it’s because the first thing people tend to know about me is that I’m an athlete who plays badminton, and then everything else is superfluous information that doesn’t matter. That’s what I go out and do every day – I mean I’m gay every day as well, don’t get me wrong – but at the start it was just like a little bit of something for me to signify that.

“Every LGBT+ person knows what a rainbow means, but some people don’t. Some people might just think you’ve thrown a wee rainbow into your bio because you like them. At first it was wee signifiers as an internal, bold act, and now I’m more confident talking about it.

“We literally have media training on how to deflect questions to stay in a safe zone, you’re absolutely allowed to say no comment or that’s not what I’m here to talk about, but I’ve never been asked a difficult question in a badminton interview in my life.

“It’s all about how your match was or who you’re playing next. That’s why Suzi said there was no information about me being out on the internet, because I’ve never really been asked about it. It’s something I’m getting more confident talking about.”

Badminton is like many other sports in that there are a distinct lack of male LGBTQIA+ players in the professional game. Perhaps that is why Gilmour is keen to spread her message, with her approach to badminton on the court and her identity off it bearing striking similarities to each other.

“I’ve always been aware that I don’t want that to be the biggest part of my personality,” Gilmour stressed.

“I don’t mind if it is, but I don’t think it’s the most interesting thing about me, even though I also want people to know that it doesn’t impact my ability to run around at all. It’s just to show that we need more representation of people being queer and open and happy, and just doing their thing and not hiding.

“It just takes any kind of other thoughts away, it makes your brain less cloudy. Not so much in my personal life, or my love life, but 2018 was a particularly hard year for me. I was doing a lot of travelling by myself, and I felt very isolated.

“That had nothing to do with being LGBT+, but when you’re wrestling with other stuff it does take up brain capacity when you’re performing. You almost have to be stupidly positive sometimes to step on court against the world number one and think you can beat them. You have to have that thought even if you are ranked 20 or 30 in the world, otherwise what are you doing? You might as well just play one point and shake their hand.

“If you’re dealing with other things, it does have an impact on performance, so I think one does inform the other.

“For right now, I’ll gradually get more confident talking about it I daresay, and I’ll maybe figure out a real message that I want to get across. Right now I guess I’m just chatting about it and getting some exposure.

“I’m going to get ‘make good choices’ as a tattoo, just because I really believe in that. Not in a karma-type way, but I just think that if you’re consistently adding to the good choice pile, then a good outcome is far more likely.

“I spoke with my psychologist a few weeks ago, and we spoke about doing things in good faith, even if it’s a hard thing to do. Always think about the people round about you, and do things with the best outcome in mind for the most amount of people.

“Make good choices is part of that, and then the whole life imitating sport thing too – in life if you’re making good choices and trying to be a good person as often as possible, you will get good outcomes.

“The same goes on the court. If you’re making wild, erratic choices and there’s no standardised form to it, you are going to have a good performance and then a bad performance. If you consistently make better decisions on your shots and your behaviour on court, then you’re going to give yourself a better chance of the outcome that you want. Make good choices is a little life motto I suppose.”

Gilmour will be hoping that good choices carry her through to a successful Commonwealth Games in Birmingham later this year – the fourth of her career.

As well as being in an increasingly good place personally, professionally her training is as good as it has ever been, which is cause for optimism ahead of what is sure to be a hotly contested battle for medals in the summer.

“It’s mad – if I stop and think about 20-year-old Kirsty, I just played that 2014 Commonwealth Games,” she added.

“It wasn’t like a head down, here we go approach, it was just me thinking ‘this will be fun, won’t it?’ I was so naive at 20 years old, I just allowed myself to go in and do it.

“It was helped by the buzz of Glasgow at that point, but like I say all three of my Commonwealth Games – I can’t believe number four is this year, I’m old man – have been so different with that internal feeling and the external atmosphere of the Games.

“I went from no pressure, to a bit of home pressure, to expectation at the Gold Coast. Then it was like ‘you’ve got a medal, now you have to get another one or it’ll look like a downward trajectory’. I know externally that’s how it would have looked, but with the moving parts and the change of players with a new generation, a lot can happen in four years with people coming up and people falling off.

“To have two Commonwealth medals, I’m pretty happy with that. When people ask what I want from my career, I would always say that I want to medal at the four major events – Europeans, Commonwealth Games, World Championships and the Olympics.

“We’ve arguably got the easiest two of those in the bag, but we’ve got the tricky two still to get.

“I’m so excited for the next three years. The place that I’m in with the coaches, the support that I have and the squad that we’ve been developing over the last five years, I think the next three, four or five years are going to be interestingly exciting.

“I think I have to look at it that way. It’s number four, and I think I’ve proven myself enough now. I’m learning how to deal with that expectation and I get better each time at picking a tournament and targetting it.

“I’d say this is the most methodical and thought out training plan I’ve ever had in terms of physical preparation and maintenance, and how focused and concentrated we are on it.

“In the past with coaches it has been like ‘we’ll work hard in this bit, then come down a little bit’, but the data we’ve gathered over the last three years and how we’re able to apply that and manipulate it gives us the best chance of performing well at something.

“My confidence builds every day going into these big events. You just know you’re giving yourself the best chance, and the quality of the women’s singles at this coming Commonwealth Games is going to be the highest it’s been for the last 15 or 20 years.

“It’s going to be mad, there are five or six people realistically vying for those three medals, so it will be a tough old time.”

Leave a comment