The last six years have been a tumultuous time for Professor Anson Mackay, but running has played a key role in getting them through.

The 59-year-old, who grew up in a tiny village on the north coast of the Scottish Highlands called Brae Tongue, realised they were non-binary decades after first coming out as gay – and just months before being diagnosed with cancer.

Back in their schooldays, they were inspired by the pop icons they were seeing on TV to play around with gender norms, but at a time where even homosexuality was still illegal in Scotland it only served to make them a target.

Boarding at school because of the distance to the nearest secondary school, they were subjected to bullying from their dorm mates in the form of electrocution and having bottles of aftershave emptied on to their bed, eventually leading to them toning down the make-up and original clothing they were wearing by the time they moved to university.

“It was the early 1980s, and it was all about new romanticism and gender bending when you had Annie Lennox and Boy George,” Mackay recalled.

“I always thought it was weird in a sense how people were able to accept those pop stars on TV, which was my only link into the wider world.

“It was a conservative society, very much a patriarchal society, so it wasn’t accepting I don’t think – but I don’t know how much of that had to do with it being Highland or being the time it was in.

“The was so much demonisation of LGBTQ+ people at that time, so everything went hand in hand. People were just afraid of difference.

“Some of the difference for me came from that, and I was also quite clever as well. When I was bullied, it was really only by the people in the hostel, and only by a few people. I moved rooms in my second year, and from then it just kind of stopped.

“Most people didn’t care – and when I did come out the reaction was mostly ‘it’s about time’.”

Although the majority of people did not seem to care that Mackay was, by their own description, “camp” at school, memories of that bullying had a lasting impact.

They would move to Edinburgh first for university, going on to complete a PhD in wetlands and peatlands in Manchester and eventually becoming a professor at University College London.

Given their professional interests, the Scottish Highlands should have been a haven for them to work in, but their experiences of being in the north of Scotland mean that they try to avoid the area to this day.

“My sister died when I was 27, and I went up for the funeral and one of the guys up there started calling me slurs at the wake,” they continued.

“It was weird after having been in Manchester and London. The sad thing is that it did put me off going back home to the Highlands for a long time.

“I don’t drive, so when I go up there I have to rely on whoever is around, and I almost feel trapped. It’s such an amazing place up there, but it is what it is.

“It’s definitely a double-edged thing. I’m learning Gaelic so I’ve been up to the Hebrides, and I go up to Edinburgh and Glasgow quite a lot because I still have friends there, but I don’t really go up to Sutherland.

“There is a lot of commonality in how I developed and what my interests are now – it’s very Highlands-based, I just don’t go up there. It’s an academic, intellectual thing where I want to know about where my home was – I don’t feel part of it but I want to understand more about it.

“I see Scotland as my heritage and my culture, but it wasn’t really until I moved to Edinburgh, Manchester and London that I did that LGBTQ+ thing of creating my own family. I’ve thought quite a few times that I feel more London than I do Scottish.”

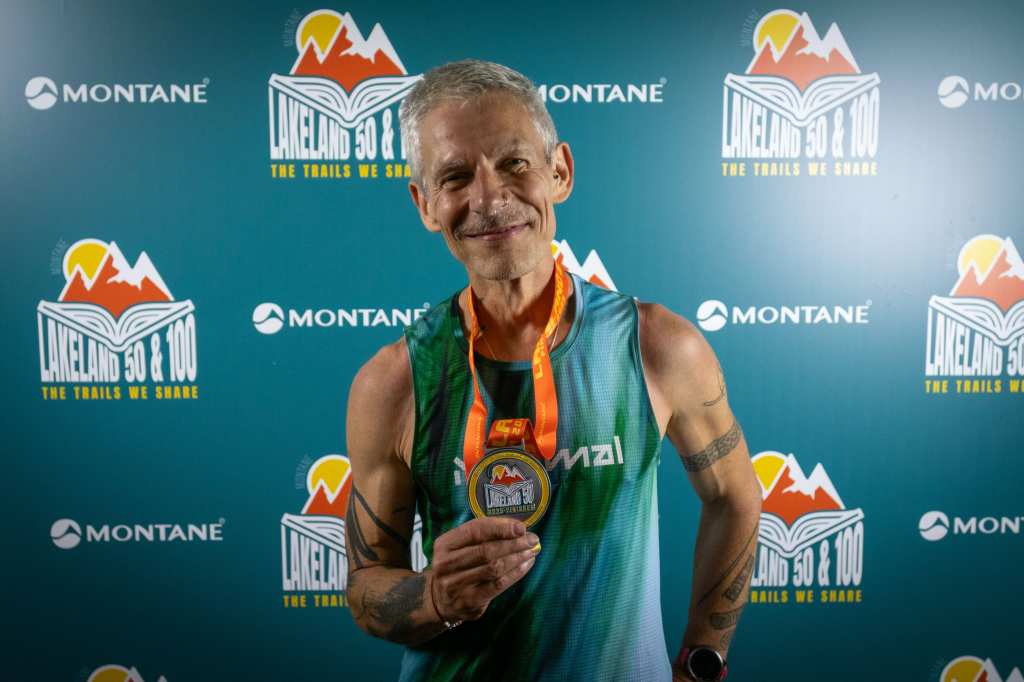

Another commonality between Mackay’s interests and what is on offer in the Scottish Highlands is their love of running. Little did they know the impact it would go on to have on their life.

While a professor at UCL, they set up both an LGBTQ+ staff/student society in Geography which would be copied across other departments, and a running group, both with the intention of providing more integration between staff and students.

Like many people will have done, going into 2020 they set themselves the goal of running every single day that year.

However, they were diagnosed with HPV-related cancer in their right tonsil which required radiotherapy treatment. At that point, when undergoing so many tests and having their life be put in doubt, running where possible became a kind of salvation – in more ways than one.

“When you have cancer, you have lots of things done in terms of treatment,” they reasoned.

“You are always having things done to you, but ultra-running was something I was in control of. In a sense, it was me gaining bodily autonomy as something that I could just explore.

“Every doctor told me not to do the running, but of course when you’re told not to do something you think ‘why not’. It’s not recognised that being active is really important for recovery from cancer, and it helps your treatment, so for me there were only positives.

“When you have a serious illness, you can be defined by it. I didn’t want to be defined by my cancer, so doing ultra-marathons took away from that and gave conversations another focus. For me, that wasn’t strategic, but it was very useful.

“Having said that, what the long-distance running also allowed me to do – which I didn’t realise at first – was think about nothing.

“My brain is processing stuff in the background all the time, and some of these long distances have you running for seven or eight hours so it becomes quite transcendental. That definitely helped me psychologically with my first run of cancer, and then with the stress of moving to stage four and getting a terminal diagnosis.

“Running allowed me to process a lot of that stuff, and then it also allowed me to realise I was non-binary. I don’t think I would ever have done that if I hadn’t been training for these long ultra-marathons.

“I was getting really upset by the anti-trans and anti-non-binary stuff from 2016, and I was thinking about what makes a man and what makes a woman, and I realised that the gender binary didn’t fit me. I think that was something I had buried since being bullied at school.

“Long-distance running has been hugely important for keeping me alive, and realising who I really am.”

At the point of realising they were non-binary, Mackay was in their 50s, so it could have been an added distraction to their cancer battle.

Indeed, they discovered their cancer had reached stage four in their lungs just months after first coming out as non-binary, so any exploration was put to one side as they focused on staying alive.

However, as time has passed they have become increasingly confident to try different fits with their gender identity – a process that is still continuing to this day.

“To my shame, when I used to see someone else coming out in their 50s or 60s, I used to wonder how they didn’t know,” Mackay admitted.

“It was really naïve of me to think that. I realised with the non-binary stuff that sometimes you just don’t know – you create a world around you, a different reality. For me, realising that was a very humbling thing.

“Another thing I’m a bit ashamed to have only just realised is that it’s not just about sexuality. Me and my partner David have had huge discussions about categories, and there is the irony of not falling into the category of being masculine or feminine but creating a new category of being non-binary.

“Sexuality is fluid over time, and I think that’s the case with gender identity as well. None of these things are fixed, and I think we are seeing more and more people – when they have the confidence – say that sometimes they are more masculine, sometimes they are more feminine, but they aren’t at either of the extremes. That makes so much more sense to me.

“I was literally out for a run and came to this realisation that I wasn’t in the gender binary. That’s all it was at first, and I played around with the terms genderqueer and genderfluid, and I settled on non-binary.

“It was absolutely euphoric, but two months after that I got diagnosed with stage four cancer so I had to prioritise staying alive. My mental focus was on other stuff.

“I didn’t go back in the closet, I just wasn’t running around telling everyone. All the attention was on whether I would live, and I how I was responding to medicine and all that stuff. Maybe that gave people time to process it.

“When I got further through my treatment and I was a bit more comfortable with how I was, I started exploring again and I would talk about it a bit more.

“Now I think I am much more comfortable with not wearing jeans and a t-shirt – I can dress up a bit more flouncier than normal, or wear some jewellery or paint my nails. When I was at school, I did all of those things, but it got pushed back inside of me.”

As well as running helping Mackay come to the realisation that they are non-binary, it helped provide a support system for them.

They are a part of the Queer Runnings club in London, which mainly consists of other non-binary and trans runners. That means the conversations can cover the realities of being gender non-conforming in a group of people who can relate to that topic, helping everyone feel freedom to express themselves fully rather than having to hide.

As for the competitive ultra-running world, Mackay has seen progress be made, but even within supposedly inclusive events they believe there is still a long way to go.

“You want to feel comfortable with the group you’re in – if you can’t talk about you who are, you are hiding yourself,” they said.

“Realising I was non-binary in my mid-50s, I’m not going to hide it from other people any longer, and especially not in a space I love.

“It’s about acceptance. Having a group who knows you are trans or non-binary, or that you might be gay or lesbian or whatever, and that accepts you for who you are is hugely important to make that run comfortable and fun. Running is one of my passions, but I can’t do that if I feel like I can’t express myself.

“I think there is actually still a bit of prejudice within the LGBTQ+ world towards gender non-conforming people. It feels like there is still a bit of distrust there.

“I’ve been going to FrontRunners’ annual queer 10k since 2010, and as of two years ago they still didn’t have a non-binary category. They put it down to their computer system which really angered me – they are meant to be the premier LGBTQ+ running group in London, and you couldn’t enter their races as a non-binary person.

“Any time I’ve done a race in the last few years, I’ve been in touch with the organisers to push for a non-binary category, because I won’t tick one of the two boxes they put out. It’s quite difficult and annoying at times, but it is definitely getting better.

“There is a race in the Pennines that now has a non-binary category, and virtually everyone I’ve met whether that be race organisers or directors have asked how they can make it better, but I think regulations put a lot of them in a bit of a bind because if they want to be affiliated to English Athletics you need to have the gender binary.

“Most people who are running aren’t looking for prizes though, so you can open up a non-binary category. A lot of my trans friends just put down the gender they identify with anyway, so it’s still in murky waters, and there is all of this EHRC stuff that means nothing is clear at all right now.”

Passionate as Mackay is about ultra-running, they have until recently been limited in how far ahead they could plan races because of their cancer diagnosis.

When their cancer metastasised into stage four, they had six tumours across both lungs and were given a terminal diagnosis.

However, they were placed on to an innovative immunotherapy treatment that was only approved in 2020, and the results have been startling.

Having made it through two years of the treatment, they now have no signs of disease, and can begin to plan for the future for the first time in a long time – and, really, the first time ever as their authentic self.

“I don’t think I’m in remission, because I don’t think they call it that when you’re diagnosed with stage four cancer, but I have no evidence of disease,” Mackay added.

“I had to retire from work because they didn’t think I was going to see out the following term. Not many people were put on the immunotherapy for the type of cancer I had because it was approved just before the pandemic, and what they found was that most people would have a bad reaction and would have to come off it within three to six months.

“The side effects were less likely to come up than in chemotherapy, but if you did have a side effect it could be fatal. Most people would last a few months, have to come off it and get a terminal diagnosis.

“What my oncologist has told me is that there are a few of us that they know about in London who got through the whole two years with no side effects at all, and the tumours have disappeared. Hopefully, if more people make it through, that will become more common.

“My oncologist tells me we are in uncharted territory, and they don’t really know what to do with me, so as long as we go without the disease presenting itself my scans will become less common.

“It is incredible. There is always that fear before the next scan that it might come back, but I don’t know what the chances of that are at all – and I don’t think the oncologist knows what the chances are of that at all.

“When this happens, you have to think about the short-term. It’s only in the last 18 months that I have started to book races for a year’s time, because before that I could only look ahead a few months. It’s brilliant, phenomenal.

“With the cancer, and the not so terminal diagnosis, you can’t really predict what’s going to happen or who you will be.

“I definitely don’t feel like I’m this person I was when I was younger and I’m finally able to express myself. I’m sure in five years’ time I might have a different outlook – and that’s the first time I’ve ever said ‘in five years’ time’. I just think that we are always moving and changing.”

Leave a comment