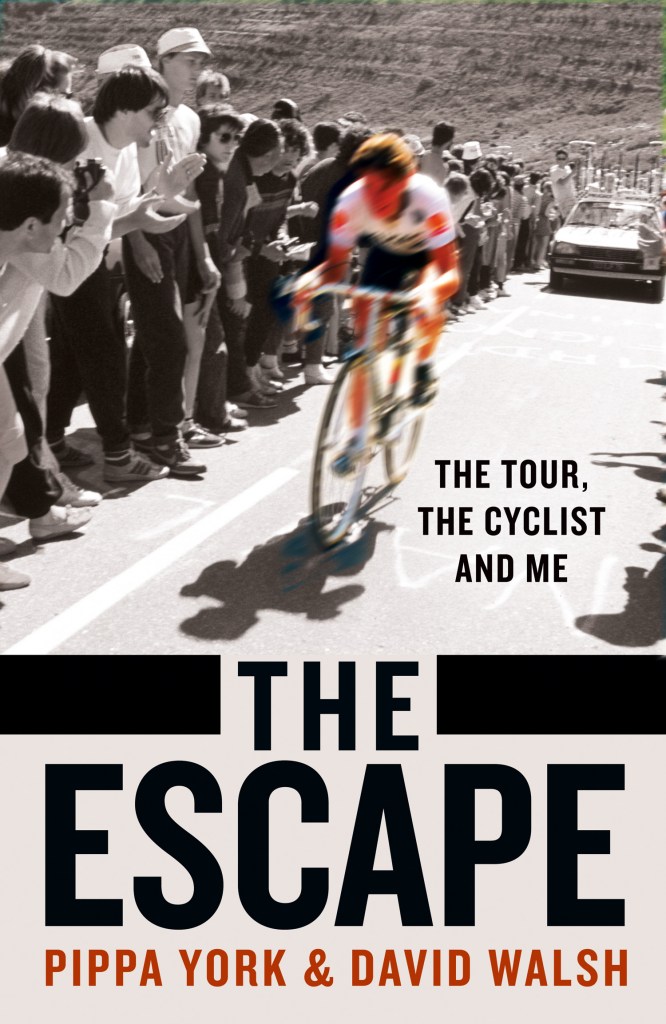

Philippa York will go down as a historic figure in British cycling. The Glasgow-born athlete made history by topping the mountain standings in the Tour De France and Giro d’Italia in 1984 and 1987 respectively, recording the highest Tour De France overall placing by a Brit until Sir Bradley Wiggins came along 25 years later.

She won five Grand Tour stages, and recorded three overall classification runners-up spots between the Giro d’Italia and Vuelta a Espana, as well as winning the Tour of Britain, in the 80s.

Now, long after her retirement from professional racing, the 67-year-old is hoping to add a different kind of accolade to her long list of accomplishments: the William Hill Sports Book of the Year.

York’s memoir, The Escape, is co-written with Sunday Times chief sports writer David Walsh, and covers her route into the biggest cycling events in the world from her working-class background, and then later in life her gender transition.

Given the often hostile rhetoric used around trans people in political and media spheres, York was somewhat surprised to see the book shortlisted, albeit feeling that trans perspectives are more important now than ever to combat what has been a campaign of targeted abuse.

“It’s quite strange (to be shortlisted) actually, because in the current climate trans life doesn’t get much respect,” she said.

“I don’t know if people are more interested in the cycling bit or the transition bit. I imagine some people will read it out of curiosity, but I can see why people find it interesting. I find it interesting and I’ve been through it!

“Things like the book are the only answer (to the hostility towards trans people). When somebody asks what you think about men in women’s sport – I gave up being a man because I didn’t want to be one in the first place, and I didn’t go through all the shit I’ve gone through to look at anyone in a changing room.

“They just need someone to blame. Things like Brexit, the price of oil, apparently these are all trans people’s faults. You can try to bring humour to these moments, but when it comes to trans women in sport the reality is they just don’t want ‘our type’ there, but they can’t say that.

“It’s not really about someone dominating whatever sport, it’s really about exclusion, and that all comes from the fear of other. People think they don’t know a kind of person, and in their mind that makes them dangerous.”

There is some irony in York having written a book, and indeed now working as a journalist and broadcaster covering cycling, given she freely admits she was not the most media-friendly athlete.

Much of that was rooted in a desire to make the absolute most of her career. For the same reason, she used to be perceived as “almost an extremist” by fellow riders for her strict fitness and recuperation regime, and also her willingness to look at other sports for inspiration in a bid to benefit from marginal gains.

In today’s world of cycling, she believes she would have progressed far more quickly given the extra support and information athletes benefit from, but when it came to working in the media York once again found herself starting from scratch.

“When I was racing you could say I was difficult, offensive maybe – David Walsh says he was scared of me,” York laughed.

“The really strange thing about journalists and the media is that they are very quick to criticise. You are doing the analysis, but you can praise the good bits and then you move on to the bad bits. I applied that to the media that spoke to me.

“I was perfectly capable of reading what they wrote, or listening to what they were saying, and not everyone likes that kind of analysis of their work. On a few occasions people would get really upset with me, and then the next day when they wrote their piece it wouldn’t go well for me.

“For me it was a strategy to not have to waste 30 minutes of my time when I could be resting and recovering for my race the next day. I basically decided which ones I would actually give some time to, and the rest I would give one word answers to.

“My reference point for that was John McEnroe and Martina Navratilova, it was their approach of ‘if you’re not as professional as me why am I even bothering to talk to you’ which I latched on to straight away.

“Starting to then work as a journalist was quite intimidating. I was stepping into a world where I was at the bottom of the hierarchy.

“I apply my standards of professionalism to what I do as a journalist, so it was difficult to do interviews and not be more nervous than they are in case I messed up and asked a really dumb question.

“I still felt that pressure from the inside, but I have found the media world a lot more friendly than I thought it was going to be. I didn’t think journalists and media people helped each other as much, I thought it was just as cut-throat as it was on the competition side but a lot of people were actually really helpful.”

Although York regularly wrote articles after her retirement, for a long time it was under her former name.

The turning point there came in 2017, when she was asked to join the ITV4 commentary team after her transition, and was faced with the reality of coming out publicly in order to explain where her expertise came from.

“You can’t be a sporting expert as a random person plucked from the bus stop, so they would have to explain who I was,” she reasoned.

“Working in the media, I decided to take control of it and write the article and provide the pictures, where nobody could ask any more deep questions and it would all be out there.

“That’s what happened, so I wrote the first edit and then passed it through friends, who passed it on to others to do more refinement of it. We really kept it under control, but it is still quite scary because you never know what kind of reaction you’re going to get from people.

“That’s one of the interesting things about transitioning, people who you think will be okay with it sometimes aren’t, and then people who you think will want to come and beat you to death can be fine, totally okay with it. It’s strange, because what has any of it got to do with them? It’s one of those things where people seem to take a position quite quickly.

“I’m aware that I’m basically the only gay in the village when I go into a press room. I’m aware that there will be people in there who might be offended by my presence, but I have to function, so I accept that as part of the life I live.

“Not everybody is accepting, for whatever reason. That’s their problem, not mine as long as they don’t make it my problem.

“I just try to be a decent journalist, and be constructive in my analysis and not pick apart people in a cruel way.

“I have empathy for the athletes, but I also have to be careful not to be too far on their side. It’s a presumptuous thing to say I’m an expert, but I do have some insider information on what’s going on in certain moments, so I can try to explain why certain people messed up.

“You can write it in a way that sounds like they are just not good enough, which I try not to do, or you can write it in a way that’s sympathetic.”

On paper, there was the perfect opportunity for York to have a homecoming as her authentic self when the 2023 UCI Cycling World Championships came to Glasgow, based practically a stone’s throw from where she was born.

However, there was no sign of her on the coverage. Frustrating though that was, York sees it more as a missed opportunity to celebrate cycling heritage in Scotland, and she does not expect anything to change when next summer’s Commonwealth Games returns to the city.

“It wasn’t just about me not being there as Scotland’s best road cyclist, what really shocked me was that all of the people who worked in the background, all of the grassroots people who have been involved for decades, they weren’t involved in any of the podium presentations,” York stressed.

“That’s not a major part of the event, but you usually see them there, being included in those moments, and there was none of that.

“If you were a local person, you didn’t see anybody you recognised in those moments, and I thought that was appalling. If you haven’t got people you recognise doing those presentations and other media work, what’s the point? How are you going to thank them and inspire other people to get involved?

“It’s not even a reward really, because every other championship that I’ve been to has those people who have been around for 50 years up there, and you shake their hands. They get their moment of being recognised for their input, but there was none of that, so I thought it reflected on Glasgow really badly.

“It will be the same people organising the Commonwealth Games next summer, and it was the same people organising it in 2014. It’s the same group of people who go round organising these events, and they are only interested in keeping their place.

“The sporting politician is somebody who is not good enough to survive in a real political context. They don’t have the knowledge and the contacts to survive in that world, because it’s a jungle and they’re not smart enough.”

Although York makes a distinction between parliamentary politicians and sporting politicians, recent years have seen the two worlds increasingly collide around trans inclusion in sports.

A host of governing bodies have banned trans women from competing at any level of their sport, with signs that the International Olympic Committee are set to follow ahead of the 2028 Games in Los Angeles, and many feel those decisions have largely been made as a result of the political climate.

In an interview with The Guardian earlier this year, York commented that she believes trans people are more understood now, but not more accepted, and on a similar theme she believes it will take a seismic political shift for any progress to be made on that front.

“We would need a change of government, and a change of politics,” York insisted.

“This is a political thing, not a historical thing. It’s worrying now being a trans person, because if anything happens anywhere in the world by someone who happens to be trans – or happens to know someone who is trans – then it becomes every other trans person’s fault.

“It’s mainly a trans women thing, because God forbid anyone finds you attractive. That’s what it comes down to – what if a straight man finds you attractive? It turns into the gay panic, where they think they have to murder you because they have been ‘deceived’.

“The latest thing is that if you go out, and a trans women happens to bump into a straight man, if that interaction turns sexual she has to tell him she is trans because otherwise he will have been sexually assaulted. It puts that women in a position where she could be subject to violence, because she doesn’t know what the reaction is going to be.

“It is being presented as something that will lead to revulsion. The law is basically saying ‘you are so revolting, you have to warn people because if someone has a sexual interaction with you they are being abused by being in contact with you’. In what way am I accepted into society under those circumstances?

“In what way has the government legislated for my existence? It hasn’t. Wes Streeting is the perfect example of an angry gay man who hates himself. Basically, Wes Streeting is a poor man’s Peter Mandelson.

“People laugh when I say things like this, but they have no depth into what it means when you are negotiating your own life as someone on that queer spectrum.

“I went from being at the top of the patriarchy, that sporty person who came from nowhere and entered into that top hierarchy, appearing to be a straight, white, sporty male. There isn’t anything better than that, but now I’ve gone practically to the bottom of the other side as a trans female.

“People that organised the Glasgow World Championships don’t want me to be seen. I’m an undesirable to them, and they think I’ve done this so I can hang out in women’s toilets.”

With so much discourse focusing on trans athletes, York is in rarified air of having been among the very elite in her sport and also having gone through a gender transition.

Her perspective should be one that is constantly sought by decision makers to give valuable insight, but until that happens all she can do is implore people to look at historical evidence with objectivity rather than getting caught up in a moral panic.

“I wish they would just look at history – where are these trans people who dominate sports? There aren’t any,” York added.

“When someone asks me if I support men in women’s sport, I have started to ask who it is we are referring to? Tell me the trans world record for the 100m, remind me of the last trans person who won a women’s road race or track title and what time they did?

“The response then becomes ‘what if’, and that’s the basic premise. It’s victimhood, the idea that people could be a victim of this and therefore they won’t let that happen.

“Sport is seen as the Disneyworld of perfection. The normal world doesn’t exist, it’s only the best people, but someone running 5000m then jumping over a water splash is someone we should aspire to be, even though it’s not relevant to the real world.

“I don’t know the numbers, but say it’s one in 10,000 people who do sport that become a world class athlete – then you would need 10,000 trans women for one to reach that level. Is that unfair?

“It all kicked off with Lia Thomas, and she won one race out of the five that she entered at college level. That’s not world level, but that wasn’t deemed to be fair that she could win one race out of the five that she entered and not be close in the others. People seem to have lost the objectivity of looking at results.

“I never knew this when I started transitioning, but according to a lot of people I turned into an elite athlete, so I’m now banned from doing the 400m. As part of my transition I have apparently gained this superpower where I can run, throw, jump and swim faster than anybody else.

“You can’t help but laugh. It’s so obvious apparently that as someone who is born male, I have this sporting superiority over everybody – all 5’7 and barely 10 stone of me is apparently this super athlete.”

Leave a comment