The following article uses a pseudonym ‘Ahmed’ to protect the identity of the person interviewed

For many, the relationship between their LGBTQ+ identity and religion is a complex one. For Ahmed, though, his faith directly led to accepting his authentic self.

Growing up in the 80s and 90s in a Muslim community in Glasgow presented its own set of challenges, but on top of that there was a distinct lack of LGBTQ+ representation and what Ahmed describes as “a lot of toxic masculinity”.

That, understandably, led to a hesitancy to be his authentic self. The idea of a thriving queer scene was something that could only be seen on television when areas like Soho in London were represented, and definitely not something that was accessible.

At least, that was the case until Ahmed got the chance to visit London at 16 years old. However, it was anything but the safe haven he hoped it would be.

“For cultural and religious reasons I was always afraid to be my true self,” he reflected.

“I really felt that by going to London this could be my opportunity to live my life on my own terms. However, when I went to the first gay bay in London I was met with racism, which was really difficult for me.

“I had imagined Soho and the LGBTQ+ community to be so welcoming, but that’s not what happened. It was like a punch in the stomach, and I ended up going back home literally the next day on an eight-hour bus.

“This was a bit of a turning point in my life. I started to internalise my feelings, especially around my sexuality, and I became quite angry at the gay community. I ended up getting in trouble with the police, and that was because I really hated myself and I wanted to push friends and family away. It was a form of self-harming if I’m being honest.

“I wanted to be someone who was straight, just like my friends and the people around me, and I put a lot of pressure on myself. I was depressed, and in a suicidal state. I didn’t have anybody to turn to – we have to remember this was before the internet, so the reality of it was that I didn’t know anybody.”

Without a support system in place, Ahmed turned to Islam to find a sense of purpose. In his own words, it is a lifestyle as much as a religion, but while being Muslim has only helped strengthen Ahmed’s other foundations of identity, with it still comes challenges and discrimination from others in both the religious and LGBTQ+ communities.

“Honour plays a big part in black and brown communities – you have these invisible shackles to keep up appearances, and unfortunately that had an impact on me and others in the community,” he continued.

“As a Muslim, I felt very comfortable in terms of myself. I prayed five times-a-day, so I always had this running dialogue with a higher power. That was my way of coping with my sexuality and it really helped me through the process of accepting myself.

“Halal food helps nourish our bodies, and when we pray it is these acts of worship that give us a sense of belonging. For me, Islam actively promotes a balance and an equilibrium of body, mind and spirit.

“What I want to say to people is that our gender or our sexuality does not prevent us from living a Muslim lifestyle – rather it is our culture around organised religion that poses problems. This is the case with Christianity as well, it’s the community around that religion.

“There isn’t always a safe space for LGBTQ+ people who identify as Muslim. We sometimes feel like we’re a sore thumb sticking out.

“At times I have been confronted with people asking me why I am Muslim. They can’t understand that you can be gay and Muslim. I’ve been in the middle of a nightclub with someone asking me about Sharia Law when I’m just there to have a good time, dance with someone and listen to some music.

“For many queer Muslims, going to these types of places can be quite off-putting. It’s just not a fun experience when you have to defend your religion when you’re there to relax and have a laugh.

“A lot of the time I don’t really go to gay venues to be honest. That’s for many reasons, but one of the main reasons is that sometimes we don’t even get past the door.

“There are two gay bars in Glasgow, and I’ve never been in the ‘main’ one because I’ve never been able to get past the security guards. They just look at me, and one actually asked me if I knew it was a gay bar – at that point I didn’t know what to say.

“This isn’t just my experience – a lot of my friends who also happen to be people of colour have come across venues who are gatekeeping from marginalised communities. That includes people who have disabilities, as a lot of the gay venues are not suitable for people who require wheelchair access or have mobility issues. It’s really sad that we are still not there when it comes to inclusivity.”

While being both Muslim and LGBTQ+ has led to issues from each side, though, a significant turning point for Ahmed came from a pilgrimage to Mecca.

Seeing that he was struggling, albeit not knowing the full reasoning why, Ahmed’s family suggested a trip to the holy site. His mother had always wanted to go, and although he went along with it more to support her, it proved to be a life-changing moment for him too.

“Initially when my mum proposed that I go to Mecca, I was not feeling religious at all – I didn’t really want to leave the house,” Ahmed explained.

“I had nothing to lose, so I did it for my mum. We went, and from the start it was really eye-opening. There are certain processes you do during the pilgrimage, and one of them was a day where you have to spend time with yourself in the desert – away from whoever you have come with. That was quite powerful for me.

“I realised that you come into the world yourself, and this is how the world is, so if you’re not comfortable with yourself you’re not going to be comfortable with anybody else.

“Another part of the pilgrimage was a metaphor – you throw tiny stones at the devil. There are these three big rock-face pillars, and you throw pebbles at it to denounce those demons inside yourself in a metaphorical way. You see people furiously throwing those stones, and those can be the feelings of not being happy with your body, or something to do with your confidence – all those little voices that say you are not good enough. Hitting the pillars is symbolic of hitting hose feelings, so I found that very therapeutic.

“Another part of the journey is that men can shave their hair off. This isn’t a necessity, but the vast majority of people do it. It’s a sign of letting go of the old you, and allowing the new you to grow.

“I loved my hair, so I didn’t want to do it at first, but it was such an amazing experience that I went for it and completely shaved my head. That was very therapeutic as well to let go of all these negative feelings and thoughts, and start a new chapter in my life.

“I felt the whole experience was very individual. I had initially thought I was going to be helping my mum, but it was about me and my journey, and my mum and her journey. That made me more spiritual, and it was there that I finally accepted my sexuality.”

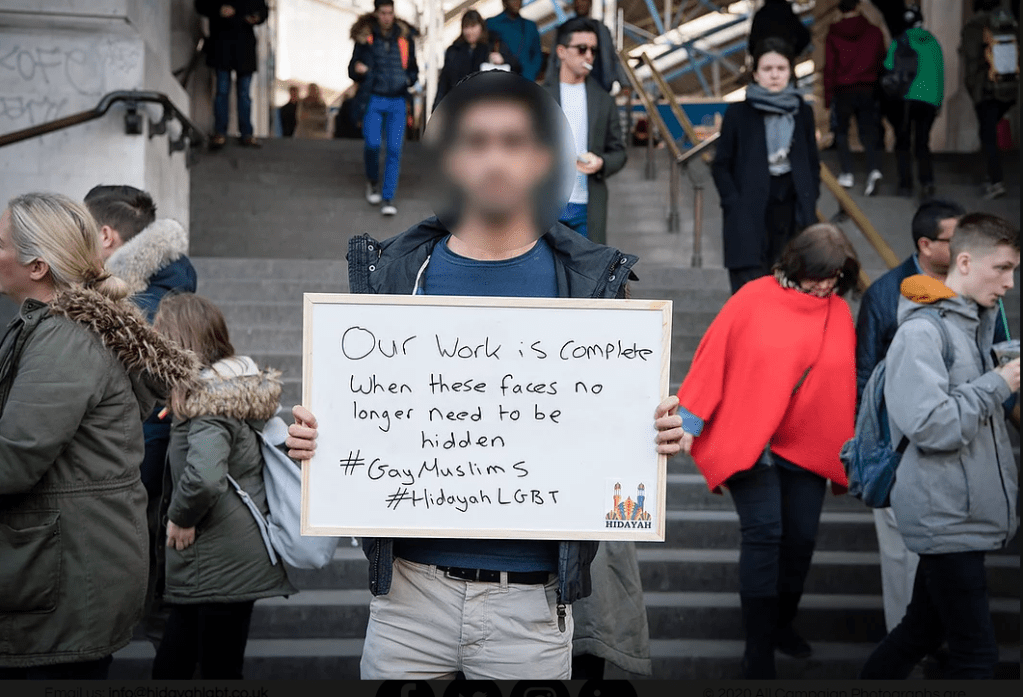

Upon returning to the UK, Ahmed resolved to make positive changes in his life, and he came across the charity Hidayah.

Named after the Arabic word meaning guidance, the charity aims to provide support and welfare for LGBTQ+ Muslims and promote social justice and education and the community to counter discrimination, prejudice and injustice.

It was through Hidayah that Ahmed discovered the Glasgow FrontRunners – named after the 70s novel which also proved inspirational to Ahmed – which opened a number of doors in the LGBTQ+ sports field too.

“I was shocked, because I had never heard of a gay running group,” he recalled.

“Another shocking thing was that it literally ran through my community. I had seen these people running, but didn’t know at all that they were an LGBTQ+ inclusive running group. That got me interested, because I realised that if I didn’t know it was an LGBTQ+ running group, the people in my community won’t know either, and it could be a safe space for me to go running and make friends and possibly meet someone.

“There were a mix of people from various backgrounds, which I found really refreshing. It was nice to be around people who were non-judgemental and just accepted me for who I am. It was incredibly affirming.

“Once again it was a bit of a turning point for me, because here were people from the LGBTQ+ community who were friendly and nothing like my first experience of LGBTQ+ people.

“In fact, I formed some really close friendships with some of my fellow runners who I’m still friends with today. They shared their experiences and their trauma, and we now support each other mutually.

“It also empowered me to start thinking about sport in bigger terms. I decided that maybe I could do marathons, and I started looking at sport as something more than just a hobby. I ended up running quite a few marathons, and it also gave me an opportunity to help the community. I became a sight-guide for people who are blind and wanted to raise money for various reasons, and in a sense I wanted to give back to the running group as well because of how they helped me, and help someone else who would enjoy sport but struggled.

“I learned to not give up, and to look after my body in terms of my diet and routine, so it made a difference for me.

“Because I had now met many other sporty people, I then started playing badminton and volleyball as well. I’m now going through a phase of trying different sports and finding myself being able to use those skills again.

“I remember that growing up, PE classes in school were terrible. That put me off team sports, because there was a lot of macho aggressiveness, and if someone would get hurt the teachers would use derogatory terms and call people ‘gay’.

“That really further internalised my feelings, so I pushed back against doing team sports. I really thought I didn’t want to be around toxic people, so I never got into team sports until recently, and that is thanks to Leap Sports.”

Ahmed now helps to run an inclusive badminton club, which is open to people from all social backgrounds, ability levels, sexualities and gender, as well as those with mobility issues. Couple that with being a sight guide, and the idea of giving back has become a prevalent one in his life.

That, again, is influenced by his religion, as well as seeing first-hand the impact that sport has had on his life and wanting others to feel that same benefit.

“One of the five pillars of Islam is charity, and charity isn’t always monetary – it can be about giving back to the community,” Ahmed added.

“The prophet Muhammad says that what you want for yourself should be what you want for other people. When I’m enjoying sport, I want other people to enjoy it as well, and I want to make it easier to bring along other people because I now have access to that space.

“I remember the days where I didn’t have anyone helping me. If I can be a pillar of support for someone else, that is what makes me happy in life. I love being around people and I enjoy anything which involves working to support people and making their lives better.

“It’s still not easy for people like myself, who have various facets to our identity. Being a person of colour, being Muslim, sometimes the day-to-day pressures of life can be too much. You face discrimination from all aspects, and you can feel very lonely.

“That is why it’s important to have an outlet to deal with all the stresses of life, and be able to go somewhere you feel safe and are able to make friends. It’s about finding your tribe, and being able to go places and be around people who love you unconditionally without judging you.

“Personally, I am in such a good place. I have been in a long-term relationship for six years now, and I met my partner through sport.

“For someone like me who is still not out, it is difficult in a sense because I’m still living a bit of a double life. That can be a struggle, however with sport and a good community around me I have been able to manage all of those challenges, and I’m better for it.

“I am now at the point where I think it’s okay when some people don’t feel comfortable to come out. Within the western world, there is this concept that you’re not going to be happy until you are waving the Pride flag and marching at events, but maybe it doesn’t have to be all rainbows and unicorns.

“You need to be in a place where you are able to live as your true self and be comfortable, and I think you can still do that with the right support and people around you.

“I’m really in a happy place. I am very luck to be in a place where I have good friends, my family are happy and I am in a loving relationship with a partner who is willing to accept that I might not come out, and he might never get to meet my family.

“For a long time I thought that I would never meet someone because of the ‘baggage’ that I come with, but it’s nice to know that you can meet someone. You just have to put yourself out there and not be scared of meeting new people, because that is the biggest challenge.”

Leave a comment